Community News

From the Librarian’s Desk: Criminal indictment of Miners on railroad bombings

Published

11 months agoon

By

BenGil Staff

After discussing my last article with Jim Alderson about the miner’s strike and march on Gillespie, he mentioned about a criminal indictment of miners on railroad bombings. This again made me interested in this article. In doing some of this research I’m amazed at the history of the Gillespie area and related coal mining stories. I really do not think the community is aware of all the national stories centered on this once vibrant industry.

Starting in the 1920’s, the United Mine Workers were under the control of John L. Lewis. Lewis was a very powerful and influential labor leader. Within the American Federation of Labor (AFL), the Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO) was formed by Lewis to include the UMW and other industrial like unions, like the United Steel Workers. Lewis controlled the UMW and thus controlled the miners.

Under his guidance, the UMW made many significant moves to increase the power of the UMW authority. All of this came at the expense of individual miners and their local unions, especially in Illinois. In many cases, Lewis’ decisions sided with coal operators and hindered labor friendly contracts. This included the policy of job-sharing arrangements. This customary policy was to allow all “locals” to share work-loads meaning if one company mine was idle those idle workers could share the work in another company mine. Basically meaning, all miners help each other and share the hours; everybody works, everybody gets a paycheck. This was a common practice in central Illinois. Lewis opposed this practice.

Lewis used all means possible to dominate the miners which included ballot stuffing, cronyism, anti-socialist attacks, false accusations and even armed violence. No one challenged him. He opposed local control, he wanted central control of Illinois miners.

In 1928, Lewis negotiated a cut in wages to Illinois miners from $7.50 to $6.10 a day. He expelled 24 miner locals who challenged some of his decisions claiming they were leftist/socialist radicals. This conflict with the UMW and local miners came to a head in the 1930’s Depression. Illinois UMW miners were on strike in July 1932 and again Lewis tried to force a contract on them that included another “pay cut” from $6.10 to $5.00 a day. After several failed votes overwhelmingly rejected by Illinois miners, the vote suddenly passed through questionable ballot stuffing by Lewis and claiming executive powers, Lewis again forced the miners to accept this new contract with the Illinois Coal Operative Association.

Illinois miners were furious, holding demonstrations and wildcat strikes. The first major event occurred in August 1932 in southern Illinois at Mulkeytown. Local miners headed south to support the local strike in the Benton area. A number of strikers and family supporters vary but numbers went as high as over 15,000. Fighting occurred between union miners and law enforcement. Many were shot and injured but no deaths were reported. Most believed Lewis and the UMW supported the operators in this strike. The violence was just beginning.

All this led to the organizing of the Progressive Miners of America in September 1932. The Gillespie Superior Mines and Macoupin County was the center of attention. The Progressives believed in total autonomy in their locals and to negotiate their own working conditions including job-sharing. The PWA would immediately try and regain some of their rights and the power stripped from them by the UMW and Lewis.

Anger grew quickly. A power struggle between the UMW and the Progressives began. The UMW refused to acknowledge the PWA. Individual mines were split between the two unions. Everyone wanted to work but which union would they join. The AFL recognized the Progressive Miners union but the National Labor Relations Board which protects union negotiating rights did not. The Progressives were able to negotiate their own wage agreements with the coal companies.

At the same time, Lewis and the UMW negotiated contracts with Peabody Coal Company that “only” UMW miners could work in Peabody mines in Christian County, forcing the Progressives out of work. Tensions built in central and southern Illinois.

At stake was control of union miners throughout Illinois. The Progressives tried to move into mines general controlled by the UMW. According to the Illinois Dept of Natural Resources, in 1932 there were approximately 44,000 miners in 162 mines in Illinois. The trouble pitted the UMW against the Progressives.

This event is generally referred to as the “union mine wars” in Illinois. Violence occurred in the form of shootings, bombings and murder. A struggle for control of Illinois mines has started. Many Progressives and their supporters were determined to make the UMW pay for their actions. Most of the violence occurred in the Springfield area.

This bloody war occurred between 1932-1935 raging throughout Illinois. Miners bombed mine properties, residential homes, and the railroads carrying coal. Most of the attacks were aimed at hurting the UMW. According to the Decatur Review, by December 1932 there were already 69 bombings in Taylorville. It got worse.

The Decatur paper in November 1933 wrote that in the first 13 months of this war there were 140 bombings and 25 deaths and by June 1934 there were 15 deaths in Christian County alone since this “mine war” began. By the time the violence seemed to decrease in August 1935, the Review claimed there were over 200 bombing and 36 deaths.

Government authorities sided with the coal operators and UMW. With the violence decreasing by 1935, many PWA miners returned to work. With pressure from the coal companies, the government decided to go after indictments on those responsible for some of the violence.

After multiple railroad bombings, the government decided to go after the culprits. Many PWA workers were charged with federal indictments on conspiracy with the railroad bombings. The federal government got involved because many of the bombings occurred on railroads caring mail on the Illinois Central Railroad. Forty-one indictments of PWA members were issued in connection with 23 railroad bombings, six attempted bombings and one railroad bridge burning that occurred between December 1932 and August 1935. It was the first time in history that indictments were returned on anti-racketeering against a labor union. However, there were no indictments on either side for the numerous residential bombings, shootings and murder.

In December 1937 in Springfield, 36 of the 41 defendants were found guilty of conspiracy to obstructing interstate and foreign commerce by bombing coal trains. The defendants were released on bond pending an appeal. The defendants included 12 from the Springfield area, 15 from southern Illinois, and 4 from the Taylorville area included John Tatman, John Taylor and Russell Wagner from Gillespie.

The defendants were originally sentenced to four years in prison and a $20,000 fine. The US Court of Appeals reduced the sentences to two years in prison and a $10,000 fine in May 1939. Several of the defendants were released for health reasons. In September 1940, after serving 15 months, 23 were paroled, including Wagner and Russell from Gillespie. Tatman from Gillespie was not paroled.

This fight for control of union miners continued throughout the 1930’s and into the 1940’s. However, the United Mine Workers will eventually prevail over the Progressive Miners. The number of miners in Illinois gradually declined throughout the 1940’s and into the 1950’s and 1960’s. According to the IDNR, in 1940 there were 139 mines and approximately 26,000 miners and by 1960, there were only 78 mines and approximately 9,000 miners.

Unfortunately, the days of union miners are gone and the fighting is over. The Progressives have disbanded. According to Jim Alderson, there are about 5 or 6 mines in Illinois, all non-union. He believes there are no union mines in Indiana or Kentucky and the only union mine he is aware of is one in Pennsylvania.

Comments

You may like

-

MCHS celebrates the season with “Ye Olde Christmas” Dec. 5-7

-

School board approves $3.9 million tax levy request; Eyes annual ISBE report cards

-

Gillespie gears up for 4th Annual Lighted Parade and Community Tree Lighting

-

Macoupin County Clerk, Recorder & Elections Office temporarily relocating due to courthouse renovations

-

Long-serving Benld City Treasurer resigns

-

County board approves long-awaited AFSCME contract

Community News

MCHS celebrates the season with “Ye Olde Christmas” Dec. 5-7

Published

6 days agoon

November 28, 2025By

BenGil Staff

Ye Olde Christmas is the theme of the Macoupin County Historical Society’s annual Christmas Show, which will be held Friday through Sunday, December 5–7, at the John C. Anderson Home and Museum, 920 West Breckenridge in Carlinville.

“The Christmas Show is one of the most magical times to visit the Anderson Home,” said MCHS Board Member and House Manager Brandy England. “Some families make it an annual Christmas tradition to visit the Anderson Home when it is decorated for Christmas. It’s a great opportunity to get into the Christmas spirit and pick up some ideas for decorating your own home for the holidays.”

MCHS member Kendra Mize, of Bunker Hill, who has coordinated the decorating effort for more than two decades, has again marshalled a small army of volunteers to decorate all 13 rooms of the home. Each room features a themed Christmas tree, along with mantle pieces, centerpieces, tabletop decor, garlands and florals, and other special touches.

The home will be open for self-guided tours from 4 p.m. to 9 p.m. on Friday, December 5; from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. on Saturday, December 6; and from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Sunday, December 7.

“We’re very excited to offer for the first time candlelight tours from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. on Friday and Saturday,” said Shawna Ashby, who serves as a co-manager with England. “Viewing the decorated home by candlelight promises to be a magical experience.”

The final candlelight tours on Friday and Saturday start at 7:30 p.m. Admission to the home is five dollars for adults and one dollar for children ages five to 12, with four-year-olds and younger admitted free of charge.

The Anderson Home Gift Shop will be open during tour hours, offering one-of-a-kind gift items and stocking stuffers. Santa Claus will be on hand in the downstairs parlor to greet children and listen to their Christmas wishes from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. on Saturday, December 6.

While the decorated home is the centerpiece of the Christmas Show, several other features on the Historical Society’s grounds will be open. The Red Barn will be open and serving hearty beef stew, chili, homemade pies, and warming holiday beverages such as wassail and hot chocolate on Friday and Saturday.

The General Store and Print Shop will be decorated and open to the public, with the Print Shop offering its popular handmade Christmas cards and other items produced in the shop; kids can print their own blank “Santa List” to keep track of their Christmas wishes.

“The General Store offers unique gift items, including some small antiques, for shoppers to peruse,” England noted.

Local blacksmiths will demonstrate their craft in the MCHS Blacksmith Shop located on the north side of the Historical Society Grounds, with wrought iron gift items, including stocking hooks and decorative pieces, available for purchase.

The Macoupin County Historical Society’s Christmas Show runs concurrently with the Carlinville Christmas Market and Downtown Christmas events, and a free trolley and shuttle buses include the Anderson Home as a regular stop during the festivals, enabling visitors to ride from the square or the Macoupin County Fairgrounds to the Historical Society grounds.

Comments

Community News

School board approves $3.9 million tax levy request; Eyes annual ISBE report cards

Published

1 week agoon

November 26, 2025By

Dave A

Members of the Community Unit School District 7 Board of Education on Monday night voted to approve a property tax levy request totaling $3,920,295 for 2025 property taxes payable in 2026. Because of tax caps and other factors, however, the district expects to collect only an estimated $3,786,607 of the requested amount.

In addition to acting on the tax levy, the board also held a lengthy discussion regarding annual district “report cards” issued by the Illinois State Board of Education to assess school performance from last year, approved a high school band/choir performance trip to Chicago in March, and agreed to apply for a school maintenance grant of up to $50,000 in matching funds.

The new proposed levy exceeds last year’s tax extension of $3,599,569 by more than $320,726—an increase of about nine percent if the levy were to be approved at the county level. The more realistic anticipation of $3,786,607 exceeds last year’s extension by $187,038, or an increase of about three percent. A Property Tax Extension Limitation Law (PTELL), approved by Macoupin County voters in 1995, restricts increases in the levy to five percent or the federal Consumer Price Index (CPI), whichever is less. This year’s CPI is estimated at 2.9 percent.

The approved levy seeks $1,650,000 for the Education Fund while expecting to realize $1,653,831; $450,229 for Operations & Maintenance, while anticipating $438,041; $200,000 for Transportation while expecting $180,434; $35,000 for Working Cash while expecting $42,602; $174,700 for the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund while anticipating $117,788; $154,101 for Social Security while expecting $105, 248; $247,264 for Tort while anticipating $240,570; and $33,501 for Special Education while expecting $32,593. For Bond and Interest, which is not subject to PTELL, the district is levying $975,500 while anticipating the same amount.

Local property tax revenue accounts for about 20 percent of the district’s overall annual budget.

Because the levy request exceeds 105 percent of the previous year’s extension, a public hearing is required. That hearing is scheduled at the start of the board’s regular December meeting at 6 p.m., Monday, Dec. 15. In the meantime, the proposed levy is available for public inspection on the district’s website and in the district office.

Using a PowerPoint presentation, Owsley emphasized the levy request is essentially a wish list for what the district would like to raise through property taxes.

“The levy is the ‘Christmas list’ I talk about every year,” Owsley said. “If you don’t put it on the list, you’re not going to get it.”

Projecting what the district can legally seek under tax caps can be challenging because the district’s total equalized assessed valuation will not be confirmed until after Jan. 1 while state law requires the district to file its levy request before the end of December. For that reason, local school districts routinely file requests that exceed what they actually expect to receive in property tax revenue, and rely on the County Clerk to adjust the request to the maximum amount the district can receive.

“Because of tax caps, we have one shot to capture increases in the EAV and new construction,” Owsley said. “If we don’t do that, we lose it in perpetuity.”

To calculate the new levy, Owsley projected a 15.12 percent increase in the EAV—nearly double the previous year’s rate of increase. By overestimating the EAV growth, the district expects to capture the entire increase in assessed valuation when that number is finally determined.

“Even though we know the EAV will likely be around the historical average, we base our levy on a much higher amount so as not to lose revenue from new growth,” Owsley told the board. “We can do this without running the risk of overtaxing taxpayers because the district will receive no more than what we are entitled to by law.”

Owsley said relatively stable increases in EAV have resulted in a steadily declining tax rate. Since 2014 when the rate was $4.24 per $100 in EAV, the rate has fallen to $3.20 for 2024. In other words, the county can use a lower rate to generate the extension to which the district is entitled because the value of taxable property has increased.

“As long as the EAV goes up by more than the Consumer Price Index, our tax rates are going to go down,” Owsley noted.

SCHOOL DISTRICT REPORT CARDS

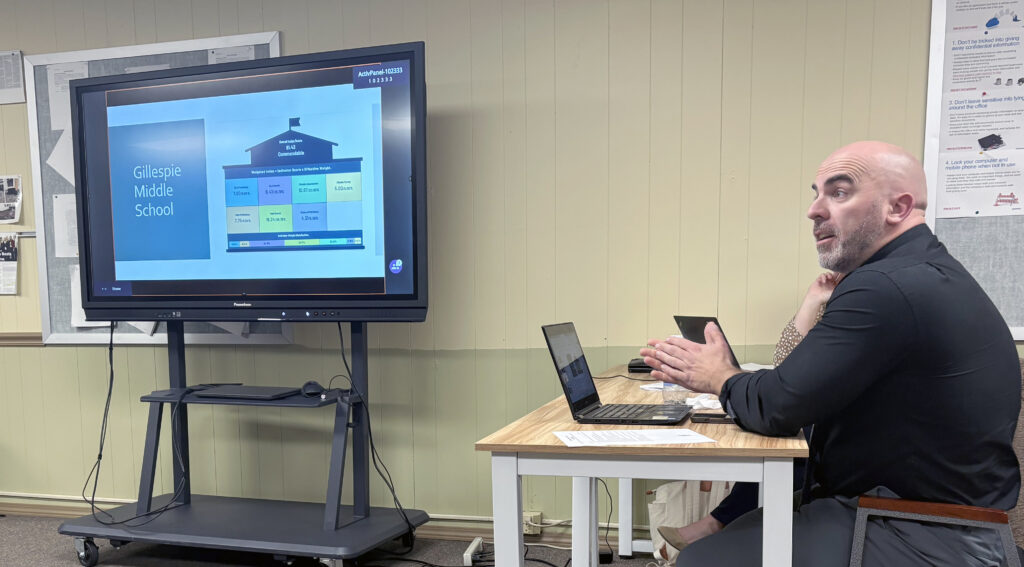

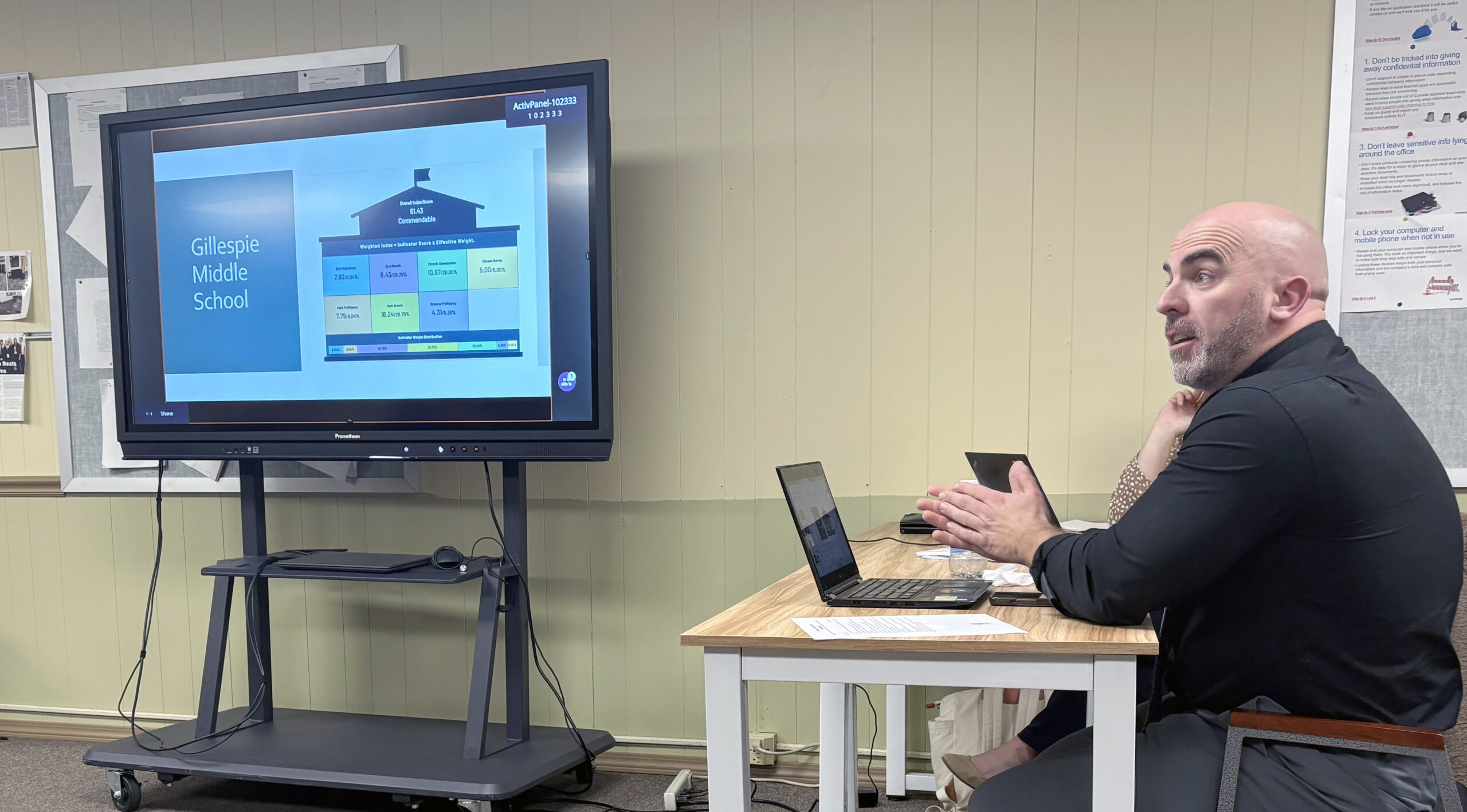

The board spent several minutes discussing recently released school report cards issued by the Illinois State Board of Education. Interested persons can view local report cards by visiting https://www.illinoisreportcard.com/.

All three attendance centers received a “Commendable” designation, meaning there are no student groups that are underperforming academically, and the high school graduation rate exceeds 67 percent. Last year, BenGil Elementary School achieved an “Exemplary” designation—the top designation a school can achieve.

Elementary Principal Angela Sandretto said administrators knew the school would not earn an Exemplary rating, even though students are state average in English/language arts, math and science. The Report Card designations are based on growth rather than academic performance. With students already exceeding state standards last year, the opportunity for growth was limited.

Assistant Principal Tara Cooper agreed, noting BenGil Elementary’s student performance is in the upper half of schools statewide that are meeting academic standards. “So, while we are not ‘Exemplary,’ we’re very happy with where we are.”

Supt. Owsley told the board the State Board of Education is working on revamping the assessment system because of the growth vs. performance issue. “That’s why they’re redoing all of this because they are penalizing schools for meeting goals,” he said.

For Gillespie Middle School, the report card shows students meeting or exceeding state averages in math and science but significantly lagging in English/language arts.

“ELA is our most concerning area,” Principal Patrick McGinthy told the board, “along with absenteeism.” The report card shows a chronic absenteeism rate of 25 percent, but Owsley and other administrators said the rate is exacerbated by the State Board of Education including nearly all absences whether or not they are excused.

Rosentreter noted the State Board will allow a student to be absent five days for illness without a doctor’s excuse. On the sixth day, however, the absence is unexcused unless the parent or guardian provides a doctor’s slip. Many parents, however, are reluctant to pay for a doctor’s visit for a child that is suffering from a minor illness.

McGinthy said Middle School teachers are attempting to address the deficiency in English/language arts by increasing writing exercises and requiring students to write in conjunction with other curriculum areas.

Rosentreter noted that the assessment standards for high schools differ from the standards for elementary and middle schools in that the State Board emphasizes graduation rates. For Gillespie, the graduation rate is an impressive 86 percent, though chronic absenteeism checks in at 31 percent.

“Math is definitely our shining star,” Rosentreter said, noting the school scored 17.8 points compared with the state average of 18. The school performed less well in the areas of English/language arts and science, scoring 16 points on ELA compared with the state score of 18 and 17.2 points compared with the state average of 19.

The report cards are based on results for the Illinois Assessment of Readiness (IAR) test for elementary and middle school students, and ACT scores for high school students.

Administrators said it’s difficult to motivate students to do well on state-mandated tests since the tests do not affect the student’s grade point average. To incentivize testing, Rosentreter said the high school is offering to let students skip final exams if they hit state standards on the mandated tests.

Owsley noted that the district report card documents the continuing decline in school enrollment—dropping from 1,325 seven years ago to 1,082 for the 2024-25 academic year.

“We don’t see that turning around anytime soon,” Owsley said. “It’s not just a Gillespie thing; it’s a trend for schools throughout Macoupin County.

BAND/CHOIR TRIP TO CHICAGO

Following a presentation by band/choir instructor Brad Taulbee, the board approved a high school band and choir performance tour to Chicago set for March 19-21. Taulbee said the tour company retained for the trip places emphasis on security and safety for traveling students. The company supplements hotel security with its own security personnel to monitor student rooms during the trip.

The tour includes workshop sessions at Vandercook College in downtown Chicago, and performances by the choir at the John Hancock Center and by the band at one of the city’s museums.

Taulbee said he is attempting to keep the cost affordable for participating students. Depending upon the number of students who ultimately go on the trip, he said he expects the cost to be about $739 per person. Additionally, he is lining up sponsors who can help with expenses for students who could not otherwise afford to participate.

“Security is my main concern,” said Board President Mark Hayes. “We just came back from there and seven people were shot in the area we were in.”

Taulbee said he expects to recruit seven to 10 chaperones and will ensure that the ratio of students to chaperones does not exceed 1:10.

SCHOOL MAINTENANCE GRANT

The board concurred with Supt. Owsley’s recommendation to again apply for a state School Maintenance grant of up to $50,000. The grant is a “matching” grant requiring the district to match grant funds dollar for dollar. The district has successfully applied for the grant for the past several years.

If the application is successful, Owsley said the funds will likely be used to remove asbestos-containing floor tiles in the choir room and elsewhere in the Middle School.

PERSONNEL

Following an executive session of about 40 minutes to discuss personnel and other issues, the board voted unanimously to accept the resignation of Tim Wargo as an assistant high school baseball coach and post the position as vacant, and voted to appoint Wargo as the head high school baseball coach for the coming season.

In separate actions, the board approved maternity leaves for Alexis Lupkey, district paraprofessional, and Gear-Up Coordinator Jordan Bartok. Lupkey’s leave is tentatively scheduled from Dec. 8 through March 18. Bartok’s leave is expected from Dec. 12 through Jan.6.

Board members voted unanimously to hire Christopher Whaley as a substitute bus driver, pending a routine background check and documentation of certification.

The board also voted unanimously to terminate Makayla Huff as a three-hour cook and post the position as vacant.

On a motion by Bill Carter, seconded by Weye Schmidt, the board voted unanimously to rehire fall coaches as follows: Jordan Bartok as head high school girls volleyball coach with Shelsie Price, as an assistant coach; Cory Bonstead as head football coach with Nate Henrichs, Jarrod Herron, Korben Clark, Alex Jasper, J.O. Kelly, Billy Gill and Florian Seferi as assistant and volunteer assistant coaches; Jay Weber as head coach for the parent-funded high school cross-country program with Jack Burns as a volunteer assistant coach; Jake Kellebrew as head coach for the parent-funded high school golf program, with Michael Otten as a volunteer assistant coach; Tim Wargo as head middle school baseball coach with Trae Wargo as assistant coach; Michelle Smith as head middle school softball coach with Jim Matesa, Joe Kelly and Melissa Heigert as assistant coaches; and Liz Thackery as head coach for the parent-funded middle school cross-country program with Laura Peterson as a volunteer assistant coach.

DISTRICT FOCUS

During a District Focus segment, Supt. Owsley introduced newly hired School Resource Officer Jacob Linhart, and High School Principal provided a report with photos of a recent school-wide Veterans Day observance.

Linhart, who has served five years as a police officer on the Gillespie Police Department, replaces Wade Hendricks, who recently retired after serving three years as the CUSD 7 School Resource Officer.

Linhart said it is a “great privilege” to serve as a Resource Officer, protecting students and staff. “I’m honored that you guys are allowing me to do it,” he said.

High School Principal Rosentreter said the school served breakfast to about 200 veterans and their families Tuesday morning, Nov. 11. Later, the veterans were joined by nearly 700 high school and middle school students for a recognition ceremony in the high school gymnasium.

Since the event coincided with the 25th anniversary of CUSD 7’s Wall of Honor program, the annual event did double duty as an induction ceremony for five are individuals, all of whom happened to be U.S. Military veterans.

The inductees included the late Sergeant Major John Marion Malnar, Command Sergeant Major John “Jack” Burns, Colonel Mark Daley, Lieutenant Colonel William P. Falke and Captain Robert Leone. Rosentreter said Daley and Leone traveled with their families from Colorado and Texas, respectively, to attend the ceremonies.

Burns, a retired CUSD 7 teacher, later visited BenGil Elementary School to present a program and teach students how to properly fold an American flag.

Rosentreter recognized the City of Gillespie for a donation of $1,000 to help purchase food for the veterans.

Born in Benld and a resident of Sawyerville, “Big John” Malnar earned a Silver Star during the Korean Conflict and a Gold Star, awarded posthumously after he was killed in action in 1968 in Vietnam. A Marine training center at Camp Geiger in North Carolina is named in his honor.

Though not a Wall of Honor inductee, Jacob Miller, a 100-year-old World War II veteran and recipient of two Purple Hearts, was recognized with a standing ovation.

The annual Veterans Day breakfast and ceremony provides students with an opportunity to meet and recognize local veterans as potential role models for their own futures.

Owsley said the event is a major event on the district’s calendar which grew out of a simple flagpole ceremony initiated 25 years ago.

CEJA GRANT FUNDS

Board members briefly discussed plans for about $74,000 in anticipated Climate and Equitable Jobs Act (CEJA) grant funds. The federal program is intended to compensate communities that have experienced revenue loss as a result of coal mine closures.

Owsley said the district committed about $86,000 in last year’s CEJA grant funds to the City of Gillespie to help pay for improvements to Plum Street, which is heavily used by district school buses. He has not transferred those funds, however, pending the start of the project.

Owsley said he was seeking the board’s input on how the money should be used.

“We could continue to partner with the city on Plum Street,” he said. “But there are plenty of project areas within the school.” The money could be used, for example, for continuing asbestos abatement. He identified other upcoming needs, including a new roof for the high school/middle school and an HVAC project.

President Hayes pointed out the school district paid for improvements to Kelly Street when BenGil Elementary was built and subsidized a project to reconfigure drainage on Broadway Street, in addition to the dollars committed for Plum Street.

“The school district is not in the business of building roads,” he said. “I think we’ve been more than generous with the city.”

Board member Peyton Bernot agreed the money should be committed for use by the school district.

TRIPLE I CONFERENCE

Several board members who attended a conference for board members and administrators Friday-Saturday, Nov. 21-23, in Chicago, commented briefly about their take-aways from conference sessions. Popularly known as the Triple I Conference, the convention is sponsored by the Illinois Association of School Boards, Illinois Association of School Administrators and the Illinois Association of School Business Officials.

Owsley said more than 700 Illinois school districts were represented, making the Triple I the largest gathering of education professionals in North America.

Bernot briefly reported on a session he attended regarding upcoming legislation and financial outlooks for school districts. He described the session as “much less optimistic” than sessions he’s attended in the past.

Owsley was among the convention presenters, discussing social-emotional learning. He commented that several districts attending reported efforts to involve students in school administrators. Some districts, he said, appointed a non-voting student representative to the school board to take part in discussions directly affecting students.

“When you think about it, we hear from faculty members and we hear from parents,” Hayes commented. “The people we don’t hear from are the most important part of what we do.”

Comments

Community News

Gillespie gears up for 4th Annual Lighted Parade and Community Tree Lighting

Published

1 week agoon

November 25, 2025By

BenGil Staff

The Holiday Sparkle Committee of Gillespie is preparing for the 4th Annual Holiday Sparkle Lighted Parade and Community Tree Lighting, set for Sunday, November 30, at 6:00 p.m. in downtown Gillespie. This beloved community tradition invites residents and visitors to kick off the holiday season with lights, music, and festive cheer.

Food trucks will line the parade route starting at 4:00 p.m., offering a variety of tasty options for families to enjoy before and during the celebration. The event will culminate in the illuminated parade and the ceremonial lighting of the community tree, signaling the official start of the season’s celebrations.

A highlight of this year’s festivities will be a special performance by Gillespie area students in grades 3 through 5. The group will join together to sing Christmas carols, lending their voices to the town’s joyous welcome to the holidays.

Parade participants are invited to bring extra sparkle to the evening—whether by entering a parade float, walking in the parade, or simply attending to enjoy the atmosphere. Participation helps make the event truly magical for the entire community. The only requirement for the parade is all entries have to incorporate holiday lighting.

To join the parade lineup, interested participants can sign up at https://forms.gle/L7Q4tEkgjj8Lt5E47. The Holiday Sparkle Committee expresses gratitude for the ongoing support of residents, businesses, and volunteers who help bring this festive occasion to life each year.

The second part of the holiday festivities will take place on Saturday, December 13 when the Sparkle will sponsor the vendor fair and food trucks in downtown Gillespie including a visit from Santa. Vendors will be located in the Gillespie Civic Center, Zion Lutheran Church, and Emma G’s Upscale Boutique while local businesses and eateries will also be open. An egg nog jog benefitting Gillespie Cross Country will also be held on December 13 and interested participants can join here.

The Holiday Sparkle Committee invites everyone to mark their calendars and join in the celebration. For more information, please contact the committee by email at gillespieholidaysparkle@gmail.com or visit Gillespie Holiday Sparkle on Facebook.